Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2025-08-14 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is the point of these exercises?

- Where do I find tutorials and documenation on Git features?

Objectives

- Get an overview of existing Git tutorials

Is this a Git tutorial?

No, this is a hands-on session for you to exercise collaborative work using Git and GitLab so that you do not have to do it with your real projects.

Take your time to do it now, not when you are busy finalizing your analysis code.

Git tutorials

Excellent Git tutorials exist, the teaching approach varies.

- Git’s website: https://git-scm.com/doc

- introductory videos

- quick reference guides

- reference manual

- Git Pro book

- curated external links

- W3 schools: https://www.w3schools.com/git/default.asp

- CodeRefinery Git intro: https://coderefinery.github.io/git-intro/

- good emphasis on “why”

- starts by exploring an existing GitHub repository

- CodeRefinery Collaborative work: https://coderefinery.github.io/git-collaborative/

- very well explained exercises for collaborative work on GitHub

- HEP Software Foundation: https://hsf-training.github.io/analysis-essentials/git/README.html

- starts by working hands-on on a local repository

- explains CERN GitLab features

Where do we start from?

For this session, you should be familiar with the basic Git workflow of commits and pushes to the remote repository as listed in the setup instructions.

- Excellent Git tutorials exist.

- Take your time to work through them.

Content from Undoing things locally

Last updated on 2025-12-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- Phew! Luckily I haven’t pushed yet — how can I change my commit?

Objectives

- Understand Git logs

- Exercise with local commits

Local commits?

Most Git tutorials start by explaining how to make local commits, track them, and use them during development on your local machine. You would have a neat list of all your commits with clear and concise commit messages. Good habit if you do!

However, in practice, many of us only run git commit

right before pushing our code to the remote repository.

Sometimes, you might want to change a commit — for example:

- You accidentally included files that weren’t meant to be committed.

- You forgot to save some changes before committing.

- Something just went wrong and you need to fix it.

If you haven’t pushed your commit yet, you only need to deal with your local repository — fixing things is straightforward at this stage.

You can find an excellent summary of undoing and recovering in https://coderefinery.github.io/git-intro/recovering/

Exercise 02.1

Create a new repository in the GitLab area.

Clone it locally and create some files.

Commit them in the local respository.

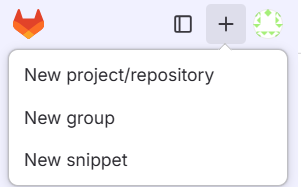

From the GitLab GUI, select “New project/repository”

Make it public and add README.

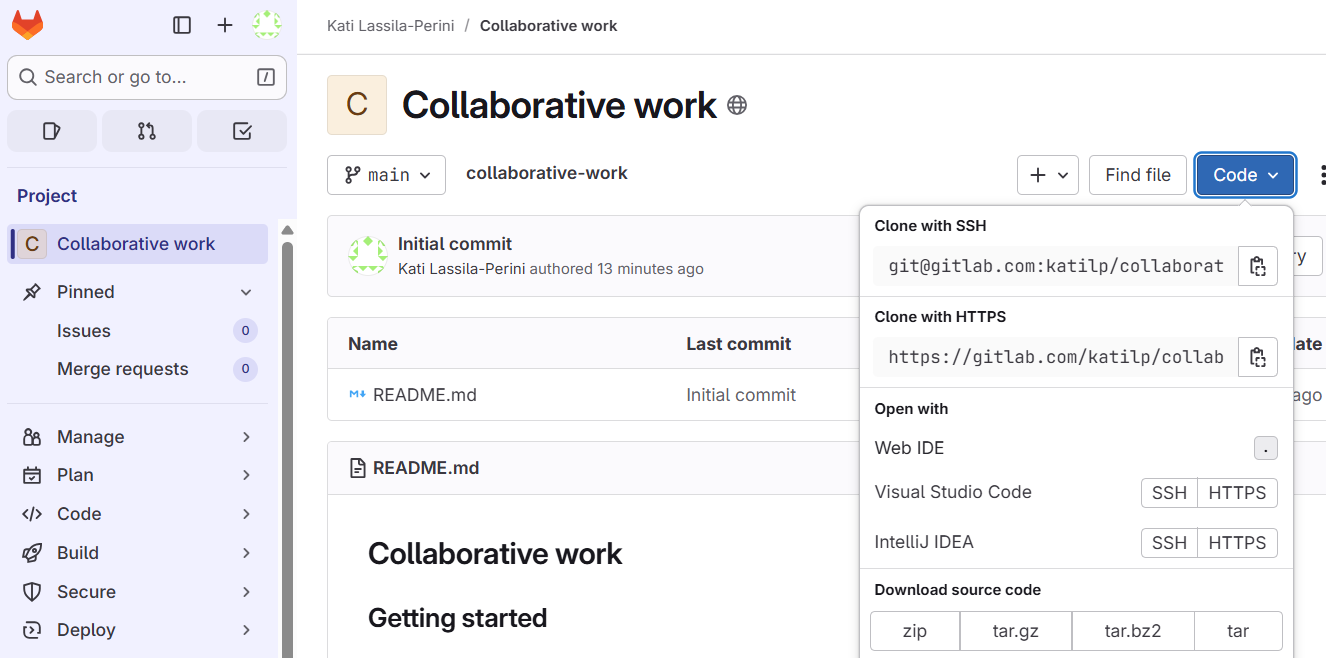

Clone it to your local area:

git clone git@gitlab.com:<your user name>/<your repository>.git

cd <your repository>Note that you can copy the repository address from the GitLab web GUI:

Create some files, for example:

$ echo "some junk" > test.out

$ echo "my real work" > work.txtShow the status of your Git area.

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

test.out

work.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)Add them and check the status:

$ git add .

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: test.out

new file: work.txt

Commit your updates:

$ git commit -m " Add my work"

[main 4cb5898] Add my work

2 files changed, 2 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 test.out

create mode 100644 work.txtInspect your commit

git status shows the local changes that have not been

committed yet.

git show shows the contents of your commit.

git log shows the commit history.

Exercise 02.2

Explore the format options for the outputs of git show

and git log. How to print logs as a short oneliner for each

commit? Can you print out just the names of the files that have been

changed in your commit?

See:

-

git log --helpor the git log documentation -

git show --helpor the git show documentation.

$ git log --oneline

4cb5898 (HEAD -> main) Add my work

339a972 (origin/main, origin/HEAD) Initial commit$ git show --pretty="" --name-only

test.out

work.txtUndoing things

The best guide on undoing things before commit is the Git documentation: https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Basics-Undoing-Things

Now as we made the commit already, we can either undo it first with

git reset --soft HEAD^ or use the option

--amend.

Exercise 02.3 - git reset

Read the example on how to undo a commit.

Then find out in the documentation

or in the git status output how to unstage a file.

Commit with your updated changes.

$ git reset --soft HEAD^

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: test.out

new file: work.txtYou can check the logs to see that your recent commit is now gone:

$ git log --oneline

339a972 (HEAD -> main, origin/main, origin/HEAD) Initial commitThen unstage as instructed, and commit again:

$ git restore --staged test.out

$ git commit -m " Add my work"

[main 3de58c2] Add my work

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 work.txtExercise 02.4 - amend

In case you did the previous exercise, recreate another “junk” file and maybe do some changes to your other files.

Stage the updates with git add . and commit them.

Now you realise that you did not want to commit the “junk” file.

Remove it from your local area and check git status. Do

as instructed to update what will be committed.

Use git commit --amend to update your commit and verify

the commit with git show.

You can do the following updates (or use your own):

$ echo "some other junk" > test.out

$ echo "Update my work" >> work.txtCheck the status:

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 1 commit.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: work.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

test.out

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Stage your updates and commit:

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Update my work"

[main 77b681d] Update my work

2 files changed, 2 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 test.outWhoops! That junk file ended up in your commit. Remove it and check the status

$ rm test.out

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 2 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add/rm <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

deleted: test.out

Update what will be committed as instructed:

$ git rm test.out

rm 'test.out'and amend your commit:

$ git commit --amendWhoa, what’s this now?!

GNU nano 4.8 [...]/gitlab-tutorial-test/.git/COMMIT_EDITMSG

Update my work

# Please enter the commit message for your changes. Lines starting

# with '#' will be ignored, and an empty message aborts the commit.

#

# Date: Tue Aug 12 16:44:39 2025 +0200

#

# On branch main

# Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 3 commits.

# (use "git push" to publish your local commits)

#

# Changes to be committed:

# modified: work.txt

#

[ Read 14 lines ]

^G Get Help ^O Write Out ^W Where Is ^K Cut Text ^J Justify ^C Cur Pos M-U Undo M-A Mark Text

^X Exit ^R Read File ^\ Replace ^U Paste Text ^T To Spell ^_ Go To Line M-E Redo M-6 CopNot familiar with NANO? Here’s a cheatsheet if needed: https://www.nano-editor.org/dist/latest/cheatsheet.html

Or change the default editor as instructed in the git config documentation.

If you are happy with the commit message, just hit Ctrl-X to exit and you will get a confirmation message of your commit. If you want to change the message, just edit it, hit Ctrl-X and confirm with Y.

Check that your commit now has only your work file:

$ git show --pretty="" --name-only

work.txt- Git command outputs are helpful, in particular,

git status. - Git is a powerful tool with a solid documentation.

Content from Undoing things once pushed

Last updated on 2025-12-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- Uh-oh! I already pushed — how can I fix my commit now?

Objectives

- Changing without breaking.

- Exercise with reverting commits.

Already pushed and it went wrong?

If you are working on your own code, you might be pushing your commits directly to the master/main branch.

We come to the collaborative works soon, and talk about using branches and protecting master/main branch so that only assigned contributors can push to it directly. This protection is a feature of the Git hosting platforms like GitLab and GitHub, not a built-in feature of plain Git itself.

For now, let us assume that you push your updates to your repository (or you are the one who has the right to do so in the common repository), so there’s no “merge request” (MR) on the GitLab side.

You’ve done your commits and now you push. You can check the contents

of your commits with git show.

$ git show --pretty="" --name-only

work.txtIt is also good practice to check your remote setting before pushing, for example:

$ git remote -v

origin git@gitlab.com:<your user name>/tutorial-test.git (fetch)

origin git@gitlab.com:<your user name>/tutorial-test.git (push)origin is a shorthand for the full address which you use

in your push:

$ git push origin main

Enumerating objects: 10, done.

Counting objects: 100% (10/10), done.

Delta compression using up to 2 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 871 bytes | 45.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 9 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To gitlab.com:katilp/tutorial-test.git

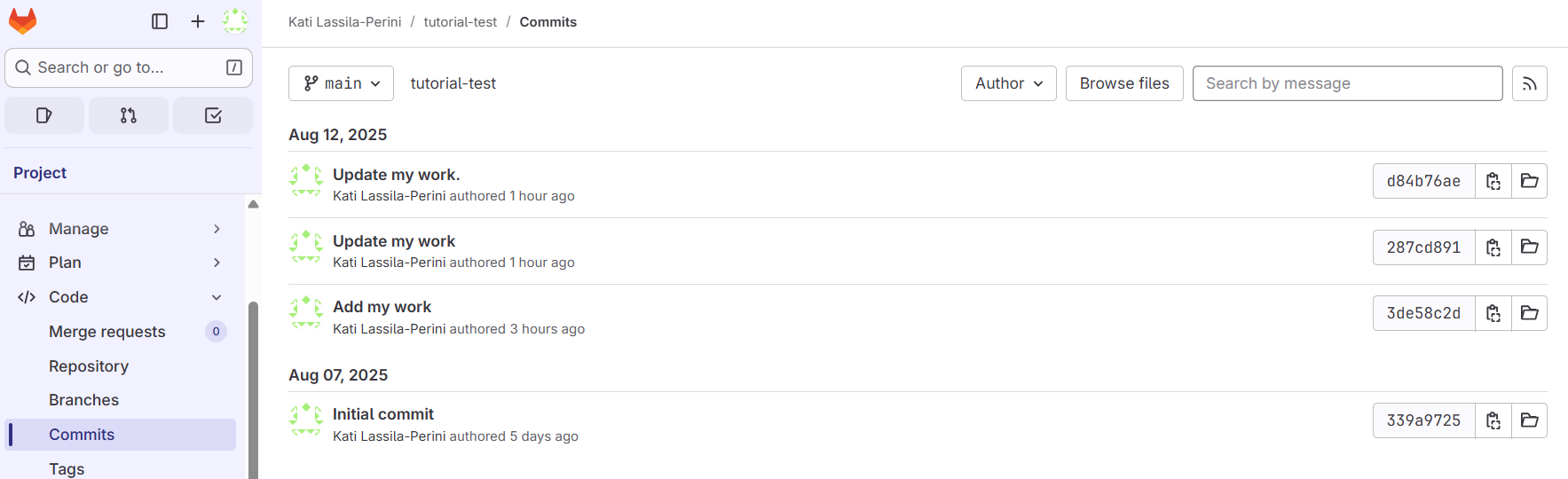

339a972..d84b76a main -> mainYou can see your separate commits listed in “History” on the GitLab Web UI, even if you pushed only once:

You can browse files on the Web UI, or inspect them in your local

area with git show <commit hash> (both short and long

forms of the commit hash work).

Now, we will exercise doing changes.

Note that amending the commit with git commit --amend

once it has been pushed the remote repository is not recommended:

Only amend commits that are still local and have not been pushed somewhere. Amending previously pushed commits and force pushing the branch will cause problems for your collaborators.

Commits can be undone with git revert. For collaborative

work, it is consider safer than git reset because

reset changes the commit history.

Exercise 03.1 - git revert

In the list of commits, undo a commit with

git revert <commit hash>.

On your local Git area, find the last commit to undo.

You will see something like this:

$ git log --oneline

d84b76a (HEAD -> main, origin/main, origin/HEAD) Update my work.

287cd89 Update my work

3de58c2 Add my work

339a972 Initial commitand you can undo the latest change with

$ git revert d84b76a

[main a77d646] Revert "Update my work."

1 file changed, 1 deletion(-)Check the status

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 1 commit.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

nothing to commit, working tree cleanand push

$ git push

Enumerating objects: 5, done.

Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Delta compression using up to 2 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 339 bytes | 33.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To gitlab.com:katilp/tutorial-test.git

d84b76a..a77d646 main -> main- Once commits have been pushed to the remote repository, make your changes so that the commit history is kept - unless you want to modify it.

Content from Working together

Last updated on 2025-12-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to best work on the same code?

Objectives

- Add contributors

- Understand roles

- Use of branches.

Let’s start collaborating!

Now we come to the collaborative work.

In general, there are two approaches:

In the fork and pull model, anyone can fork an existing repository and push changes to their personal fork. You do not need permission to the source repository to push to a user-owned fork. The changes can be pulled into the source repository by the project maintainer. When you open a pull request proposing changes from your user-owned fork to a branch in the source (upstream) repository, you can allow anyone with push access to the upstream repository to make changes to your pull request. This model is popular with open source projects as it reduces the amount of friction for new contributors and allows people to work independently without upfront coordination.

In the shared repository model, collaborators are granted push access to a single shared repository and topic branches are created when changes need to be made. Pull requests are useful in this model as they initiate code review and general discussion about a set of changes before the changes are merged into the main development branch. This model is more prevalent with small teams and organizations collaborating on private projects.

We will be using automated workflows, some of which require authentication features stored as “secrets” in the repository, and they will not be available in forks. Therefore, we choose working on a shared repository where all contributors are added as members.

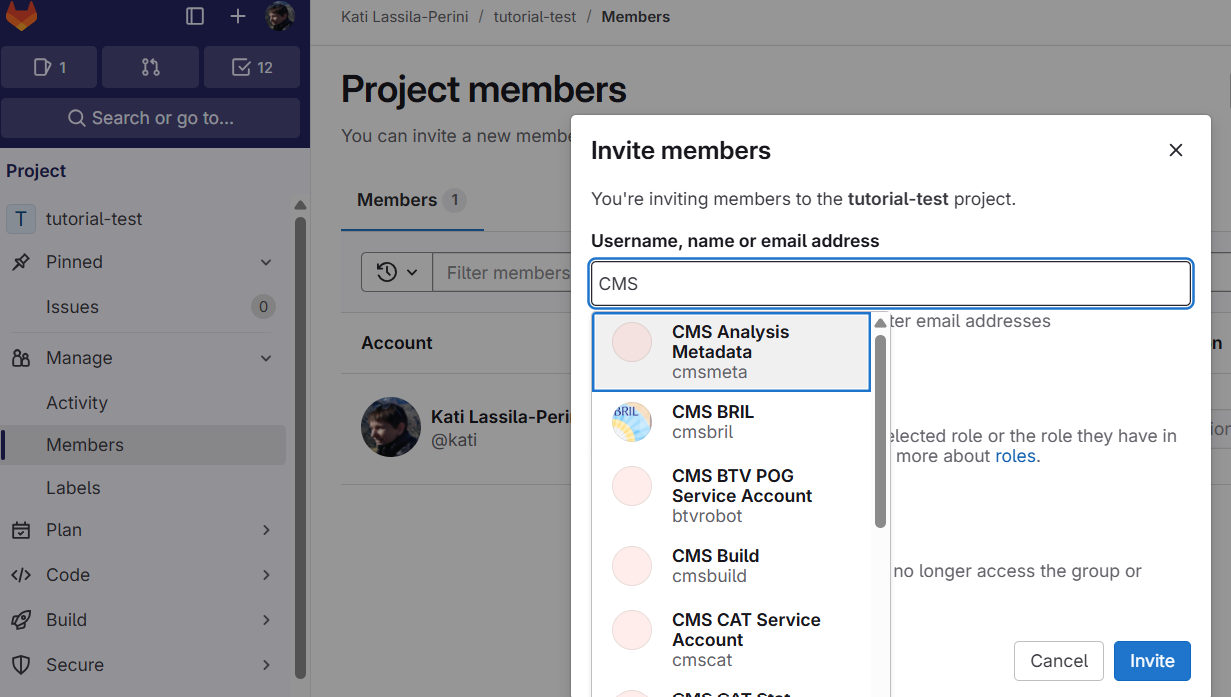

In the shared repository, go to Manage -> Members.

In the CERN GitLab instance, you can find all CERN accounts, including service accounts:

Learn about the roles.

Note in particular the branch rules and protected branches, see them in Settings -> Repository.

Only owners or maintainers can push directly to the default branch.

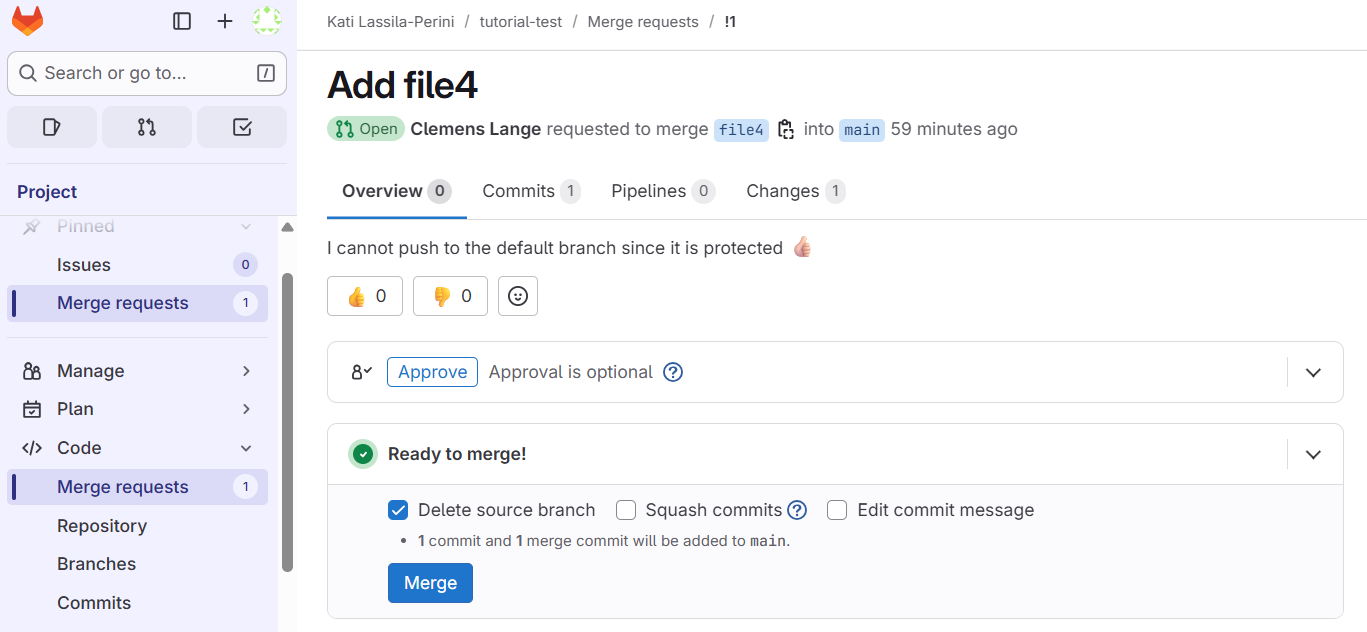

You will see a message similar to this:

remote: GitLab: You are not allowed to push code to protected branches on this project.

To gitlab.com:<project address>

! [remote rejected] HEAD -> main (pre-receive hook declined)

error: failed to push some refs to 'gitlab.com:<project address>'Make the changes with the usual Git workflow. Note that if you have a local repository with the same name, you will need to define another local name to the newly cloned local area:

git clone <git address> <local-repo-name>

cd <local-repo-name>Create a new branch:

git checkout -b new-featureDo the edits and then

git add .

git commit -m "Describe your updates"

git push origin new-feature Follow the link to make a merge request and the repository owner can review and merge it.

Browse through the tabs and see the changes. Do not merge it yet as we continue to the next exercise to test it locally.

Exercise 04.3 - checking a new feature branch locally

As the project owner or maintainer, test the new feature locally. You would do this, for example, to run some code locally to see if it works as expected.

Use git fetch origin to get the latest changes and then

checkout the new branch.

Once tested, merge the request on the GitLab Web UI and delete your local branch.

Retreive the status of the remote repository so that you know the new branch name.

$ git fetch origin

remote: Enumerating objects: 12, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (12/12), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (8/8), done.

remote: Total 11 (delta 3), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0 (from 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (11/11), 1.67 KiB | 25.00 KiB/s, done.

From gitlab.com:<project address>

395b0d5..6372999 main -> origin/main

* [new branch] file4 -> origin/file4Checkout the branch with

git checkout -b file4 origin/file4To test, you might run some code locally. If it looks OK, merge the

merge request on the GitLab Web UI. You can delete this local branch

after testing. You may need option -D to force it.

Remember to update your local main/master branch!!!

After a merge request have been merged, remember to update your local default branch.

git checkout main

git pullDo this every time when you start a new development.

You can also delete your previous branch:

git branch -d new-feature- If the use of automated workflows is planned, it is convenient to work in a shared repository instead of using forks.

- You will use branches to contribute to the shared repository (unless you are the owner or the maintainer).

Content from Resolving conflicts

Last updated on 2025-12-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to solve conflicts in code?

Objectives

- Rebasing your working branch to a recent updates in the default branch

- Solving conflicting edits in files

- Defining best practices for contributions

Enter panic mode!

Everybody is frantically working on the code repository. The owner commits straight to the default branch, developers push from their own branches… and soon, conflicts explode.

To keep the conflict on the code — not between people — we’ll practice breaking things on purpose and then fixing them.

Exercise 05.1

Exercise with your pair to add content to you shared repository in the default branch. You can do so if both of you have at least maintainer rights to the repository. Learn how to update your working area with contents of the updated remote.

One of you makes a new local edits. Meanwhile, the other one updates the remote default branch with new files.

If you try to push, you will see a message like this:

! [rejected] main -> main (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to 'gitlab.com:katilp/tutorial-test.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do not

hint: have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing to

hint: the same ref. If you want to integrate the remote changes, use

hint: 'git pull' before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.A bare git pull, as suggested in the message most likely

gives:

2f8c69a..d32176b main -> origin/main

hint: You have divergent branches and need to specify how to reconcile them.

hint: You can do so by running one of the following commands sometime before

hint: your next pull:

hint:

hint: git config pull.rebase false # merge

hint: git config pull.rebase true # rebase

hint: git config pull.ff only # fast-forward only

hint:

hint: You can replace "git config" with "git config --global" to set a default

hint: preference for all repositories. You can also pass --rebase, --no-rebase,

hint: or --ff-only on the command line to override the configured default per

hint: invocation.Get the remote changes with

git pull --rebaseand then push your updates.

Did this work in your case?

Exercise 05.2

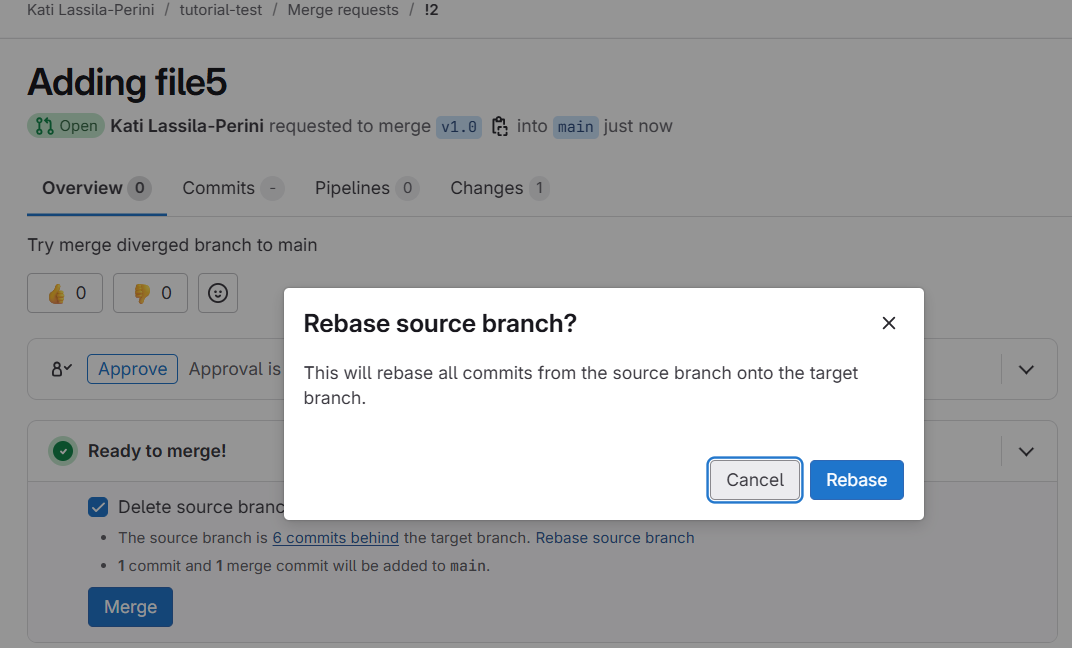

Exercise with your pair to add content to you shared repository in two different branches. Learn how to update your working branch with contents of the updated remote.

One of you makes a new local edits to a local working branch. Meanwhile, the other one updates the remote default branch with new files.

Create a new branch, make edits, and push them to the shared repository with

git push origin <your branch name>Then make a merge request from the GitLab Web UI.

If the branches diverge you will see a message about it and you can click on “Rebase source branch” and accept

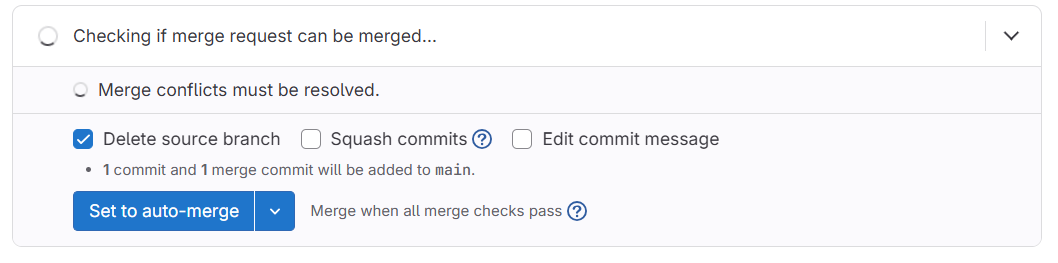

GitLab checks for conflicts

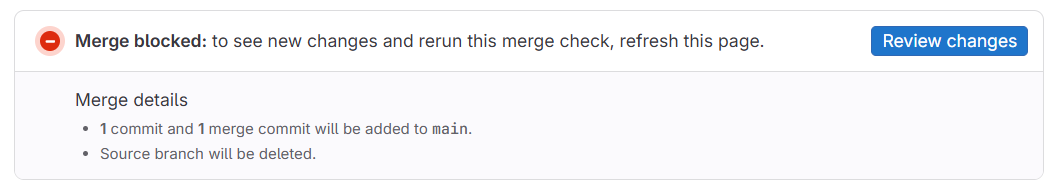

and once done gives

Follow the “Review changes” link, and if there are no conflicts, your can merge again.

Note that you could have avoided this by rebasing before pushing. You could have refreshed your main:

git checkout main

git pullthen moved to your working branch and rebased (after the local commit)

git checkout <your branch name>

git rebase mainIf there are not conflicts, i.e. edits to the same files, you would get a message:

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: <your commit message>Exercise 05.3

With your pair, make local edits to the same file in the shared repository.

One of you edits a file in a local working branch. Meanwhile, the other one updates the same file in the remote default branch.

Observe the error messages when trying to merge and learn to solve conflicts with confidence!

Exercise conflict solving on the GitLab Web UI and with the Git command line tools.

Do your edits (to the same file that has meanwhile been modified) in a working branch. Commit and push your branch to remote. Go to the branch in the GitLab Web UI and make a merge request.

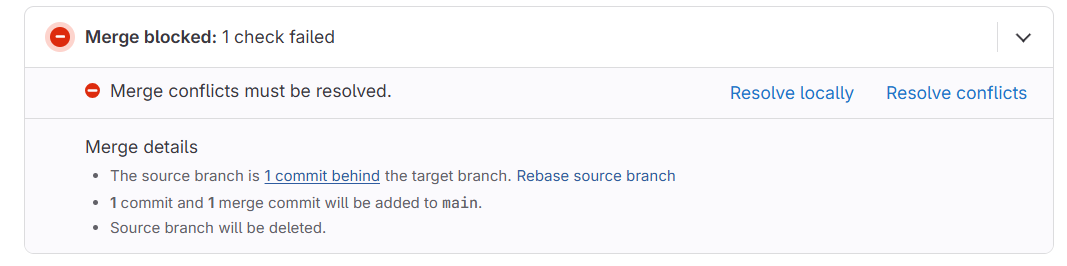

When trying to merge from the GitLab Web UI, you will see this

Clicking on “Solve locally” gives instructions to copy-paste to solve them by fetching the branch locally.

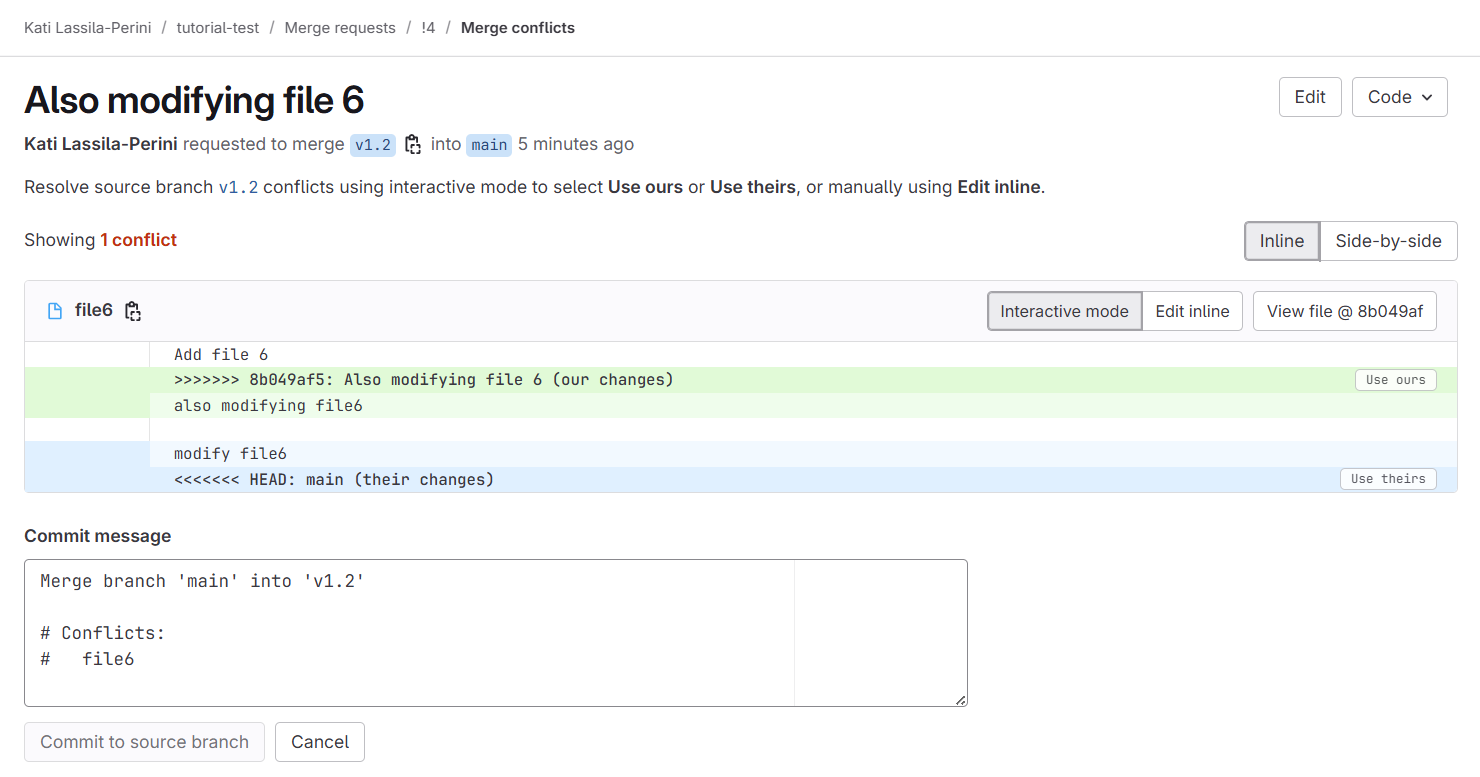

Clicking on “Resolve conflicts” gives an online tool to choose among the two divergent versions or to edit inline

Update the file as needed, commit and merge.

See also https://docs.gitlab.com/user/project/merge_requests/conflicts/

Exercise 05.4

If you have enjoyed resolving conflicts, go ahead with your exercise pair to make further simultaneous divergent changes to the directory structure and the files in the shared repository.

See below!

Avoid modifying the same files simultaneously!

Small conflicts are easy to solve but big divergences are a pain.

Organise the code and its development so that developers can work on separate files.

Avoid big, long-lived development branches!

Read this instructive comment on reddit:

A lot of people use branches as a comfort mechanism. Hiding your code until it’s ‘perfect’ feels safer. Not having your code merged until someone has spent a load of time reviewing it line by line feels safer. The reality is getting changes out there means issues are found sooner, only reviewing changes in PRs delays opportunity to give early feedback on the approach or solution.

Remember to update your local main/master branch!!!

You will avoid a good amount of problems, if you remember to update your local default branch.

git checkout main

git pullDo this every time when you start a new development.

- Git is the tool for managing collaborative work on code.

- Git automatically integrates changes when it’s safe, and asks you to resolve things when there’s a conflict.

- Conflicts are not errors—they’re a normal part of working with shared code. But resolving them is an extra step for developers or maintainers.

- Merging your work into the default branch regularly prevents large conflicts and saves effort.

Content from Keeping things in order

Last updated on 2025-12-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to use issues to keep things in order?

Objectives

- Opening issues

- Closing issues with merge requests

- Defining best practices for contributions

Keeping things in order

Whether it’s a personal project of your own or a shared repository, keeping track of tasks in issues is a good practice.

Issues help inform all contributors about missing features, work in progress, or topics for discussion. They can also be used to report bugs. GitLab lets you select from three different types of issues — Incident, Issue, or Task — but these only differ if you have defined separate templates to guide contributors in providing useful information.

Issues can be assigned to project members closed through merge

requests. The closing

can be automated by using closes #<issue number>

in the commit message. Similarly,

related to #<issue number> links a commit to an

issue, which helps tracking progress.

Issues can be labeled based on their content, difficulty, urgency, status of work in progress, or other properties. The labels can be defined for each project separately, and a default set of labels can be easily generated from Manage -> Labels. Labels are helpful in search in large projects.

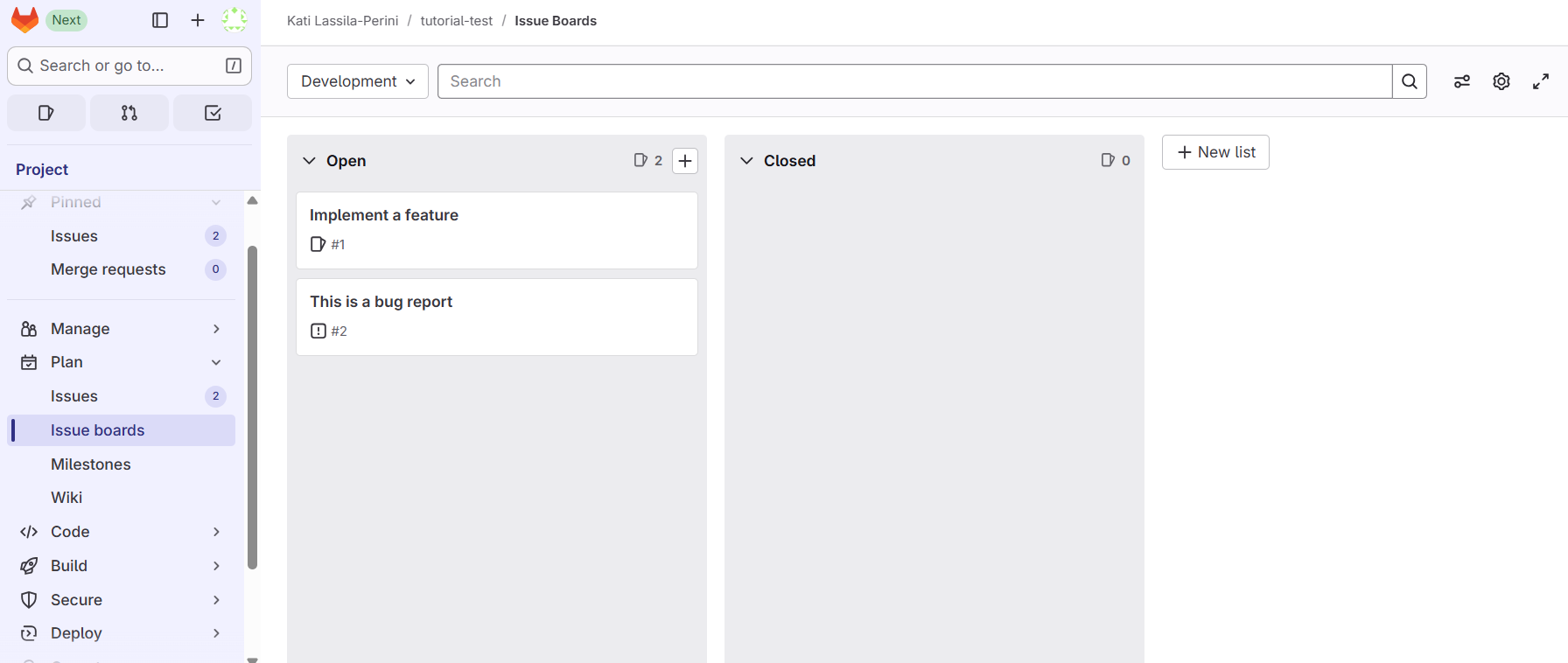

Issues can be viewed in an issue board, and be connected to a milestone. They can be set up Plan -> Issue boards and Plan -> Milestones.

Remember to update your local main/master branch!!!

Always remember to update your local default branch.

git checkout main

git pullDo this every time when you start a new development.

Exercise 06.1

As the owner of the exercise repository, describe a desired new feature in an issue. Assign it to a developer (that’s your exercise buddy). Let them make the changes suggested in the issue and push it in a branch with a commit message that automatically closes the issue once merged. Review the merge request and merge it if you are satisfied.

Use closes #<issue number> in the commit message

to connect the merge request to the issue and to close it once

merged.

Issues are useful even in single-contributor repositories

If you’re the only contributor, you’ll just be closing your own issues. Still, tracking them helps you stay organized.

Exercise 06.2

Explore setting up and using an Issue board. In addition to the default “Open” and “Closed” lists, add some others, for example “In progress” and “Help needed”.

Follow Plan -> Issue boards.

You will see something like this:

To add lists, you will first have to define the corresponding labels in Plan -> Issues.

Exercise 06.3

Make a quick list of the work you have planned for your code. For real, not for the exercise repository we have been working on.

Could you add them as issues to the code repository?

That’s on you and we come back to this at the end of the day!

- Issue tracker in GitLab is a convenient tool for a centralised discussion for code development in a repository.

- Issues are helpful for tracking the progress and sharing the work.

Content from Automate testing

Last updated on 2025-12-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to automate testing of code updates?

Objectives

- Understand basic GitLab CI/CD pipeline concepts

- Run your first CI/CD pipeline

- Define a test

- Use artifacts

GitLab CI/CD pipelines

CI/CD stands for Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery. It means that updates are frequently integrated into the codebase and their functionality is tested, so the software is close to “deliverable” at any point in time.

CI/CD pipelines are automated workflows that can be configured to run when new code is updated, or scheduled to run at regular intervals.

When developers push code to GitLab, they can define automated tasks

in a .gitlab-ci.yml file. These tasks might include running

tests, building applications, or deploying code. GitLab Runner is the

application that executes these tasks on computing infrastructure.

GitLab.com offers computing infrastructure for these tasks, and the CERN

GitLab instance has access to dedicated infrastructure at CERN.

yml (or sometimes yaml) is a commonly used

language in various workflow definitions and fairly easy to read and

understand. Keep in mind, however, that correct indentation is crucial,

as YAML uses indentation to define structure.

We will first have a look at the template that GitLab suggests in the “Pipeline editor”.

Exercise 07.1

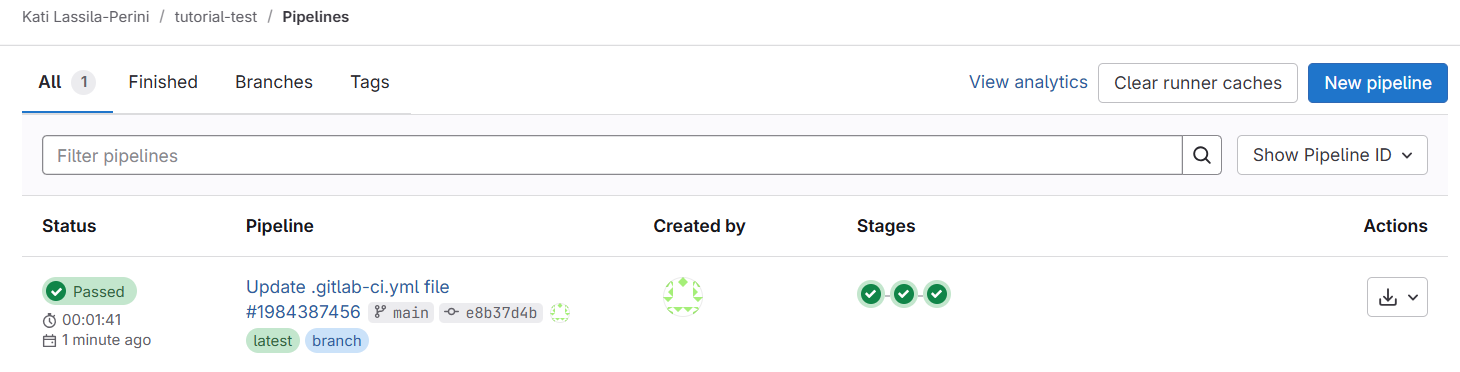

On the exercise repository, follow Build -> Pipeline editor and click on “Configure pipeline”

Inspect it, commit it and follow Build -> Pipelines to see it running.

While inspecting, observe:

- stages with default names

build,testanddeploy, see https://docs.gitlab.com/ci/yaml/#stages - that this a typical software industry pipeline structure that builds a tool that is then deployed

- scripts usually consist of shell commands (or scripts)

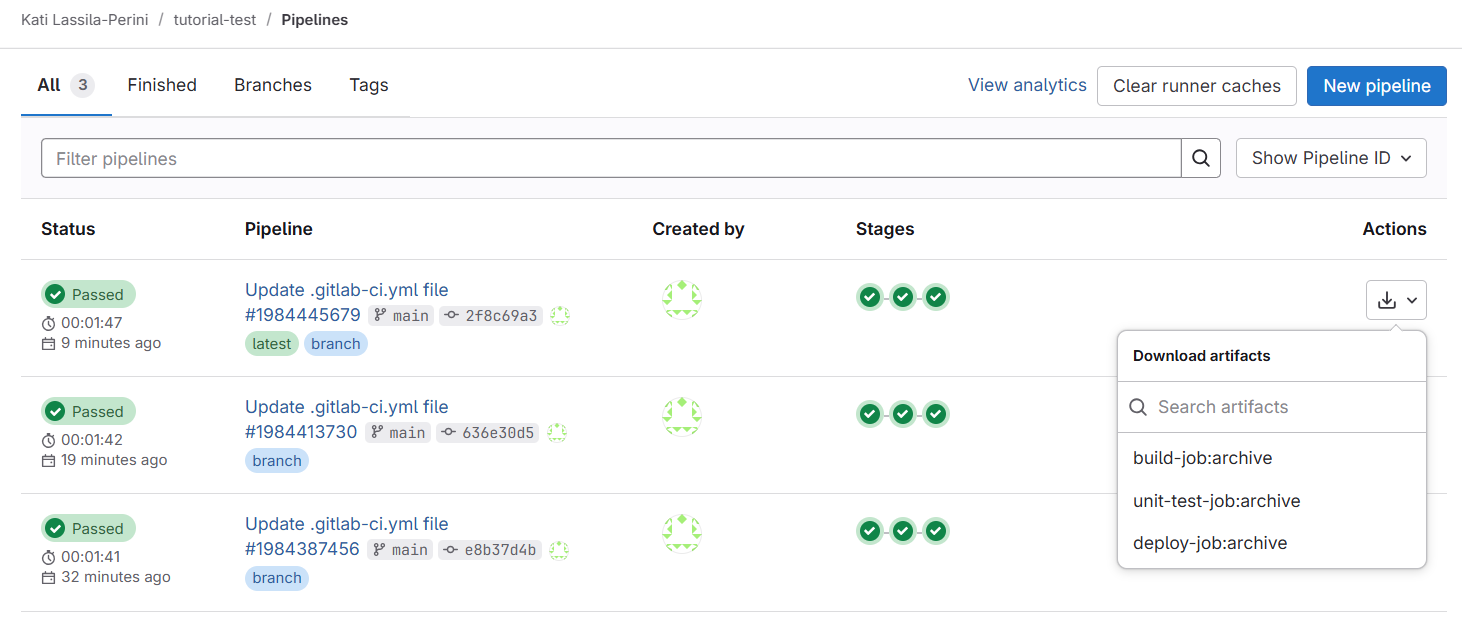

Once done you will see something like this in Build -> Pipelines:

Exit codes

Remember that in the earlier exercises, the repository owner pulled the new feature branch locally to test it. This process could also be done automatically.

To do that, we need a test that either passes or fails, which the pipeline can interpret.

Unix exit codes can be used for this purpose. Every command returns

an exit code — 0 for success or greater than 0 for failure. You can

display the exit code of the last command in the terminal with

echo $?.

You can make a script to stop at the first command that returns a

non-zero exit code with set -e.

You can read more about exit codes in the HSF GitLab tutorial.

Exercise 07.2

Exercise with shell commands. Exercise with a python test or a shell script.

Type echo $? after a command on your terminal.

Write a bash script test.sh with some commands in it.

Test what happens when you run the script.

Now we go back to the exercise repository, so just a reminder:

Remember to update your local main/master branch!!!

Always remember to update your local default branch.

git checkout main

git pullDo this every time when you start a new development.

Exercise 07.3

Add a test to the pipeline template. The repository files are available in the jobs. You could test, for example, the contents of the files in the repository, or some other functionality. Keep it simple, we’ll get to the real work soon.

Replace the default echo ... and sleep ...

commands in the .gitlab-ci.yml file with test commands of

your own. You can also add a test script to your repository and run

it.

Artifacts

In physics analysis, the outcome of the workflow — for example, a result file or a plot — is the best indicator that the code works as expected.

Such outcomes can be defined as artifacts in GitLab CI/CD pipelines, and they can be accessed through the GitLab Web UI.

You can define artifacts in the .gitlab-ci-yml file, and

they are by default available to all stages of the pipeline. Note that

artifacts cannot be modified, so if you plan to use the output of one

step and modify it in a subsequent step, you will need to make a local

copy of it in that job.

Exercise 07.4

Add an artifact to your CI/CD pipeline.

You can use something similar to this:

script:

- mkdir -p outputs

- echo "Compiling the code..." > outputs/build.txt

- echo "Compile complete." >> outputs/build.txt

artifacts:

paths:

- outputs/You can check in the subsequent job scripts that what you write in

the outputs directory is visible. Only the jobs that have

the artifacts: keyword, store them as artifacts to be

downloaded. However, even if without the keyword, the

outputs directory is available in all jobs.

You can download the artifacts from the Pipeline view:

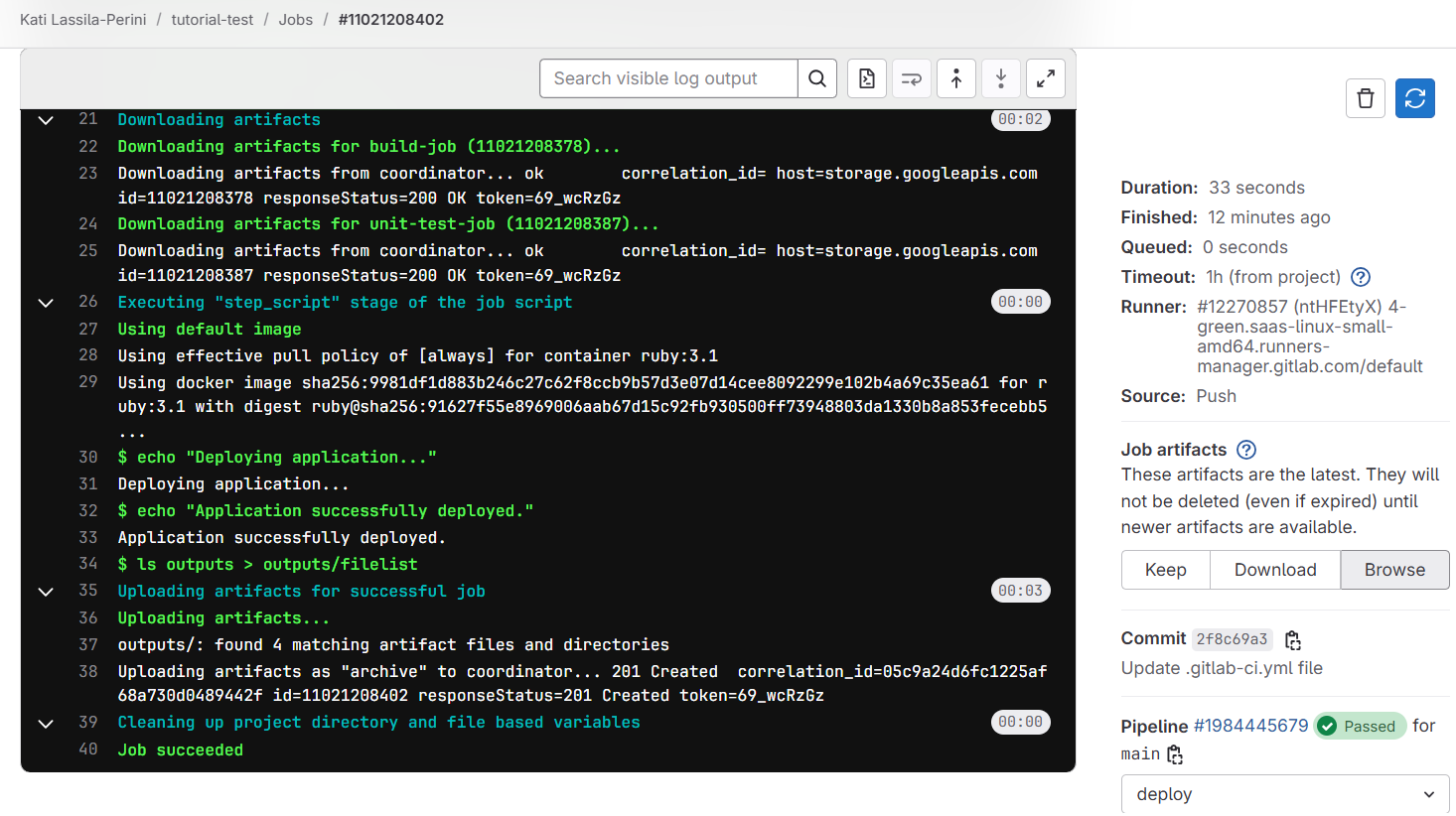

or browse them by clicking on a single job, and following “Browse”:

- GitLab CI/CD pipelines are useful to test the functionality of the code updates.

- They can perform decicated tests or procude a sample output which can indicate that the code works as expected.